It’s fascinating who you can bump into in the pub, especially now that we’re entering the post-pandemic world. In my case conversations with strangers inevitably end up with some kind of discourse about buildings, and Gareth was no exception. That’s probably because Gareth revealed himself to be an urbex fanatic – which for those in the know is that fascinating sub-culture of people who explore abandoned man-made structures, and in particular urban buildings.

Gareth and his team have recently been in some degree of trouble after being apprehended inside a local mansion house, which has been attracting a lot of local press after its owners wanted it sold off to developers, resulting in its demolition and replacement with starter homes. The property in question was Cornist Hall, a large 19 bedroomed house one mile (1.6 km) west-southwest of the town of Flint in north Wales. Built in brick and stone the Jacobethan style it was the birthplace of Thomas Totty, an admiral who served under Lord Nelson. It was owned for many years by the John Summers steelworks family who remodelled the property extensively.

In the 1980s the property passed through several owners who attempted to operate it as a wedding and social functions venue, but it eventually closed in 2012 and has since fallen into a sad state of neglect and disrepair. It is now a favourite haunt of various interest groups, including ghost hunters and Gareth’s urban explorers. This in turn has attached many urban legends to the building, including an unsubstantiated story about a bride-to-be who killed herself there after her father objected to her marriage and threw away her wedding ring. There’s even been a recent Amazon Prime documentary – the Haunting of Cornist Hall – about the ghostly white figure who it is claimed wanders the decaying corridors of the mansion in search of her lost wedding ring.

Cornist Hall is still in a pretty solid structural state, is in a great location and has huge potential for rescue as a family home or business opportunity, so it’s something of a mystery why repeated attempts to sell it or restore it have floundered. It’s a story echoed across Wales and numerous other countries where grand historic buildings have been left to decay and fall into the ground due to the lack of visionary rescue.

Unfortunately it’s not just historically significant buildings that are at risk and being ignored. Throughout the Covid pandemic our normally bustling urban centres became deserted wastelands, as the loss of vital footfall closed many shops, businesses and offices. A recent report from the UK’s Royal Society for Public Health has estimated that one in 10 high street shop premises in the UK are currently empty. Others have also warned quite rightly that we may never return to old ways of living, working and purchasing, and that there’s now an urgent need to reconsider and repurpose many of our large retail and business localities to reflect new post-pandemic lifestyles.

When it comes to rescuing neglected buildings we’re reasonably good at recognising the importance of churches, castles, country houses and ancient structures, but there’s less inclination to see beauty, relevance and more importantly usefulness in abandoned commercial properties. When such buildings are utilitarian and have no distinguishing architectural features there’s even more likelihood they’ll be demolished, and there’s a particular enthusiasm for eradicating more recent concrete and steel buildings of the immediate post-brutalist era.

It’s often argued that this kind of urban dereliction even creates spatial stigma, as these abandoned buildings tend to attract crime, graffiti and anti-social behaviour. In the early 1980s social scientists James Wilson and George Kelling introduced a theory labelled the ‘broken windows theory’, which argued that the built environment communicates to people, and a broken window says that a community displays a lack of informal social control, and so is unable or unwilling to defend itself against crime and continued dilapidation. It is not so much the actual broken window that is important, but the message the broken window sends to people. It symbolises the community’s apathy and vulnerability and represents the lack of cohesiveness of the people within. On the other hand neighbourhoods with a strong sense of cohesion care about the environment so fix broken windows and assert social responsibility on themselves, effectively giving themselves control over their space.

Whilst demolishing abandoned and neglected structures may seem attractive to many, these days we need to consider our options carefully. The very act of demolition itself has negative consequences – creating energy, water and emission footprints and whilst new buildings may be more efficient, environmental impacts extend to far more than just construction materials and methods. In many cases a creative repurposing of an abandoned building can have more measurable benefits to community and even inspire local regeneration.

Across the UK we have many examples of unlikely and unloved buildings finding new life and function, which in turn has reignited a sense of community, ownership and fresh commitments to long neglected neighbourhoods. In many respects these new uses have also prevented the incursion of speculators who invariably tear down old buildings, build new high value structures and generally gentrify neighbourhoods in a process that excludes residents and encourages population displacement.

For architects there’s a real challenge in educating society to become optimistic about revitalising obsolete and abandoned structures, especially when they are not obviously worthy or attractive. It’s fairly straightforward to put a case for repurposing an unglamorous industrial site like the Albert Docks in Liverpool or the Holland & Wolfe yards in Belfast as the history is there and such buildings have epic stories to tell. But how do you make a case for preserving an anonymous cement factory or an underground car park? Well, it’s perfectly do-able.

On the outskirts of Barcelona, a giant cement factory was constructed during the first phase of World War I–era industrialisation, comprising more than 30 silos, two and a half miles of underground tunnels, and huge engine rooms. By the 1970s, the complex had become an eyesore and a worrying source of local pollution. Demolition seemed obvious until a visionary young architect named Ricardo Bofill turned the site into a what is widely recognised as a masterpiece of postmodern architecture. After demolishing over two-thirds of the structures on the site, he worked with Catalan craftsmen to preserve the rest and the exterior of the building and La Fabrica (the Factory) is an iconic building that now opens to lush green gardens with olive trees, eucalyptus, and cypress.

Closer to home one of the best examples I can think of is the old Littlewoods Football Pools headquarters in Edge Lane, Liverpool. During World War II the building was requisitioned and became home of the government’s postal censorship department, while its printing presses were used to print National Registration cards. Its vast internal spaces were used for manufacturing the floors of Halifax Bombers, barrage balloons and woollen material.

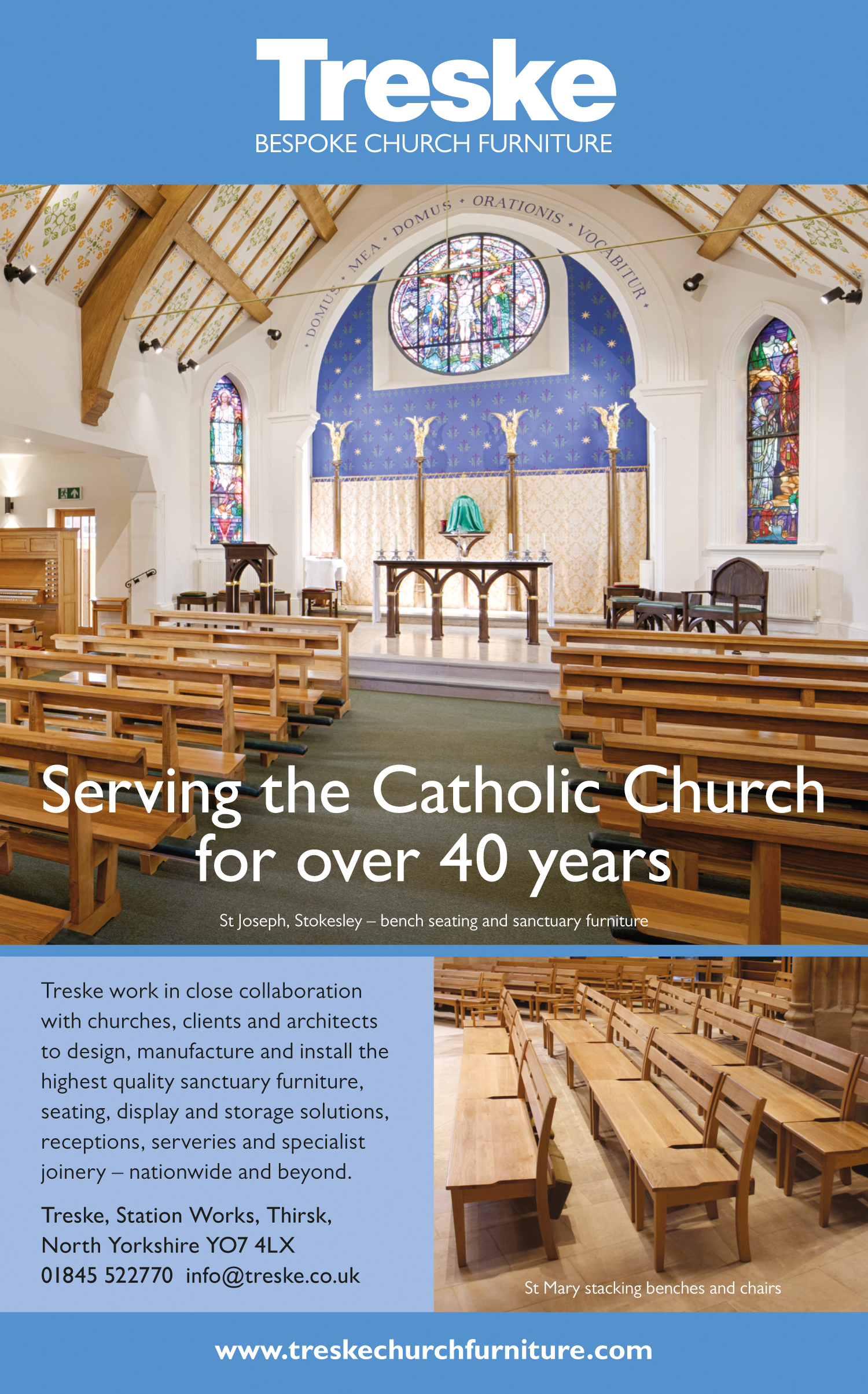

After English Heritage refused to list it and two redevelopment attempts collapsed this relatively unattractive concrete structure lay abandoned and vandalised for decades until 2018, when it was announced the building would be repurposed as a film studio complex (pictured), the new home of the world-famous Twickenham Studios. Dubbed ‘the Hollywood of the North’, work has already started on the £35m multi-million pound transformation, and the positive impact on Edge Hill, one of Liverpool’s most deprived areas, will be profound.

Taking on the repurposing of unloved buildings isn’t easy, and fraught with risk. In many cases it requires imagination and new approaches to both materials and design parameters. Architects will need to satisfy communities, planning authorities and other bodies in ways which may be radical and challenging, but the rewards are well worth pursuing.

Joseph Kelly is an architectural writer and founding Editor of Agora Journal