Over the past few days I’ve been in the sleepy north wales village of Hawarden, photographing some particularly fine Victorian buildings nestled in its snug little high street. Those familiar with the name will either know Hawarden for its modern state-of-the-art Aibus factory that is the final assembly site of wings for the Airbus plane fleet, or for being the home of British Prime Minister Sir William Ewart Gladstone. It’s also home to the famous Gladstone Library and the adjoining Flintshire Archives building. Gladstone was an avid bibliophile and for anyone interested in politics and Victorian social history the library of 250,000 books, Britain’s only Prime Ministerial Library, is an absolute must.

Given Gladstone’s early heavily conservative views and the family’s involvement in the slave trade, I never had much of an interest in the man, but the library and the nearby rambling Hawarden mansion that was his home have always fascinated me. Known as Hawarden Castle, the CADW Grade I fortified house was built in the mid 18th century and was later remodelled in the gothic style. Today the house and estate are still owned by the Gladstone family.

Just along the little high street from the Gladstone library, hidden behind a tangle cherry trees, is the detached house that was once the home of Georges Edmond Pierre Achille Morel Deville, latterly known as Edmund Dene (or simply E.D.) Morel. The house has no memorial of any kind and its residents are likely unaware of the significance – and more recently notoriety – of its once famous owner.

Whilst working in a Liverpool shipping office Morel noticed that rubber was coming in from the Congo, but only machine guns and manacles were being shipped out. His investigations led to the publication of his explosive book, Red Rubber, which exposed the horrors of native labour and resource exploitation in the Congo and eventually forced King Leopold II to sell the Congo Free State to the Belgian State to resolve the abuses. Morel enjoyed a notable career as a writer, journalist and later Labour MP, ousting none less that Winston Churchill from his seat in the 1922 General Election. But in recent years Morel’s reputation has soured significantly as it has been argued that his writings were riddled with racist attitudes.

As I wandered around Hawarden on a frosty January morning, trusty Leica in hand, I heard the news that many miles away in London a man had turned up at the BBC headquarters with a long aluminium ladder, climbed it and was busily taking a lump hammer to Eric Gill’s iconic Prospero and Eros statue. The Gill sculpture has been the subject of increasing protests in recent years, as have his Stations of the Cross in Westminster’s Catholic Cathedral, after the public became more generally aware of his sexual abuse of his daughters.

Just days after the lump hammer attack, the charity Save the Children announced that it was dropping the Gill Sans typeface from its branding. As we all know Gill Sans is a brilliant and ubiquitous typeface that has no equal, but will now almost certainly have to be consigned to the desktop trash by most typographers and designers.

Dropping one typeface amongst thousands is no particular problem, but what are we to do with the numerous other Eric Gill artworks and monuments, many of which are integral to historic buildings? When Fiona McCarthy penned her brilliant biography of Gill in 1989 It was hailed as a textbook example of how to do biography. Gill’s sexual habits were revealed in her text, but gained little more than passing comment amongst academics. Today we’re suddenly confronting not only what to do with Eric Gill and his works, but how to reconfigure countless buildings, structures and monuments. New political and social perspectives could soon force an entire reappraisal and reconstruction of our city centres, most of which were built on complex and now questionable Victorian morals.

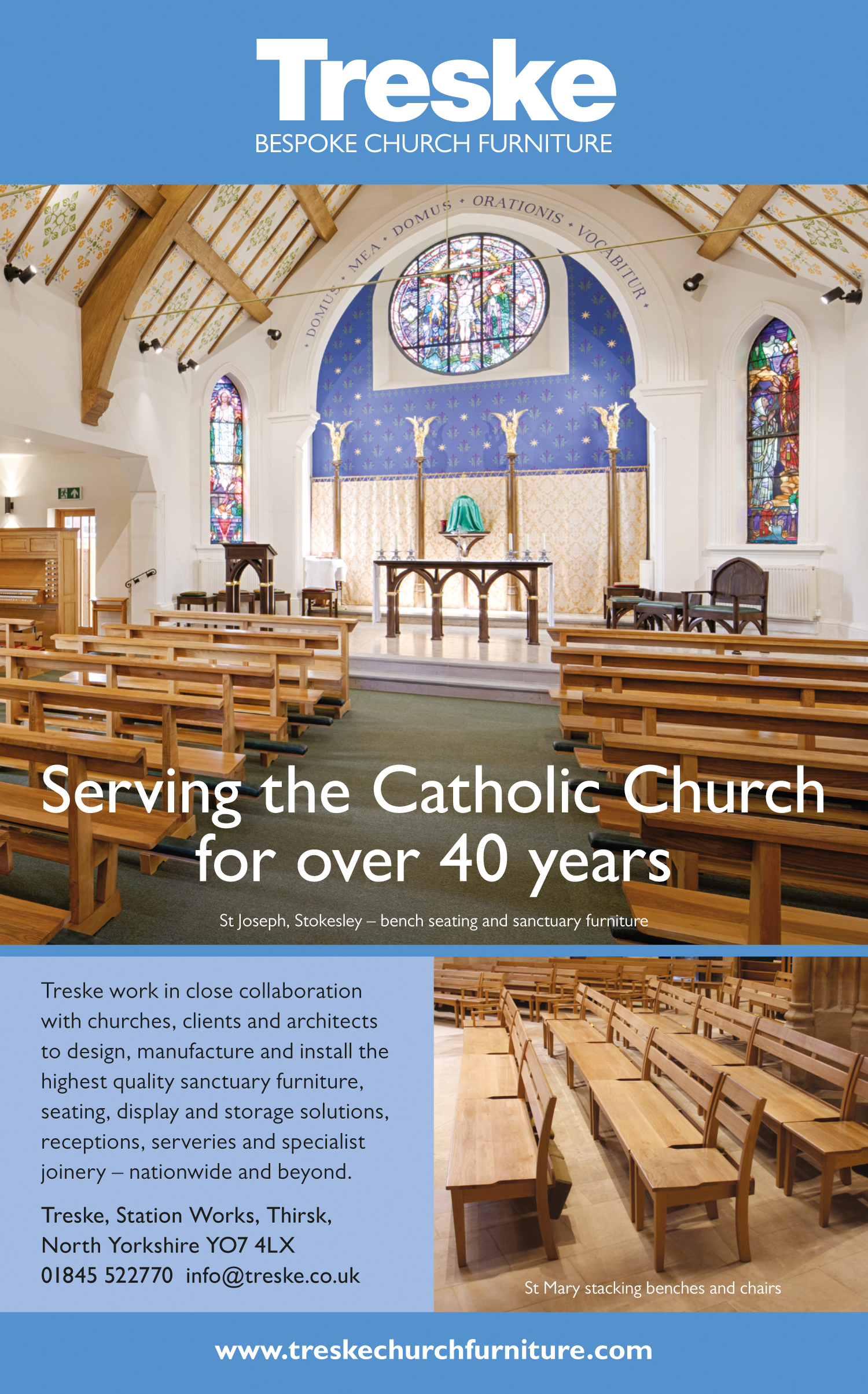

The problem, or perhaps the challenge, is illustrated well in recent events in Bristol, where a statue to Edward Colston was thrown into the docks, and civic leaders have renamed the city’s famous Colston Hall (pictured) as the insipid and unimaginative Bristol Beacon. Colston, who is currently being re-identified exclusively as a slave trader, was also responsible for many positive civic acts and funded socially important buildings in the city of Bristol – the Colston Hall was built on the site of one of his radical schools for deprived children. Whilst the good you do may not outweigh the bad you do, monochrome assessments of human achievement are at best inaccurate and at worse dangerous.

Back in Hawarden, William Ewart Gladstone is also being rapidly redefined as a beneficiary of the slave trade. His family certainly profited hugely from owning planations and the massive government compensation (about £9.5m in today’s money) that they received from having to free their slaves at Abolition in 1834. Gladstone himself defended the trade in his early years, but later in life named the abolition of slavery as one of ten great achievements of the previous 60 years where the masses had been right and the upper classes had been wrong. This didn’t stop Liverpool University last year renaming its Gladstone Hall building Dorothy Kuya Hall after a vigorous student campaign. (Dorothy Kuya was Liverpool’s first community relations officer and helped establish the city’s International Slavery Museum in 2007.)

For those working in architecture this new ideological wave has implications, because although they are involved primarily in the construction of buildings, architect’s names can become attached eternally to the buildings they create, and this can have considerable reputational consequences. This is especially the case when civic authorities dig into their corporate history for inspiration, as few of the founders and benefactors of our great cities are untainted by society’s changing values.

The reverse can also happen, where the most inconspicuous and accepted buildings can develop a sudden notoriety because of the person associated with them. Few might argue with the tearing down of Jimmy Savile’s Glencoe retreat or his top floor penthouse flat in Leeds’ Rounday Park, despite the fact that both buildings were perfectly sound structures, but a similar controversy over in New York is raising more complex questions about the relationship between buildings and those associated with them.

Philip Cortelyou Johnson was an American architect who helped define modern and post modern architercture. His iconic works include the modernist Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut; postmodern 550 Madison Avenue in New York, designed for AT&T, and 190 South La Salle Street in Chicago. In 1978, he was awarded an American Institute of Architects Gold Medal and in 1979 the first Pritzker Architecture Prize.

Despite regretting it deeply later in life and publicly expressing deep remorse for his behaviour, Johnson in his youth held extreme right-wing views and was a deep Nazi sympathiser. Few people thought anything much of this until 2020 when, in the wave of the name changes that followed the murder of George Floyd, 40 architects, designers, and educators, calling themselves the Johnson Study Group, asked that galleries named for him at the Museum of Modern Art be renamed, and other honours given to him removed from public view. Even Johnson’s iconic buildings are now under scrutiny. Despite being under consideration for landmark status and ignoring howls of protest, his AT&T building had its famed lobby ripped out in 2018 as part of a ‘remodelling’ exercise and just last month it was announced that the Cleveland Play House, Johnson’s 1983 hometown megachurch-ish structure, the largest regional theatre complex in the USA, was being ripped down to make way for a parking lot. Although the building was unpopular and derided by many from the outset, attempts to preserve this important and unique structure were muted heavily by the current reappraisal of Johnson.

The problem of separating art from the artist, the building from its benefactor, or even from its architect, is a new dilemma that will take some sorting. The new, rising cult of relativism in society means that increasingly the only viewpoint that matters is ‘how I feel about it’. By extension, if a sufficient number of people feel in a particular way about a thing, then this becomes the new reality.

Swapping the names of buildings is pretty straightforward, after all football grounds get renamed almost every season and no-one bats an eyelid. So renaming a structure that’s been attached to a negative history shouldn’t present too many problems, and at least the building and its value to its surroundings is preserved. For me that also serves to remind people that buildings are about purpose, function and service. But I can understand equally that some people will feel very strongly that by their very existence some buildings serve as a monument and reminder to their creators and what they stood for, so repurposing or renaming them might not eradicate the constant reminder they present of painful history.

I have to confess my instinct is to preserve such buildings, even if their societal value has shifted. I’d even go so far as to say it can contribute to a better contextual understanding of history. A good example is the Reichstag building in Berlin, which has sailed through the years of the Imperial Diet of the German Empire, the workers’ bloodbath of 1920, the Nazi regime and then decades of decay and disuse before being resurrected spectacularly in October 1990 by British architect Sir Norman Foster. Today it is a wonderful, airy and welcoming building that is once again home to the German parliament, and is making numerous useful contributions to its environs.

Statues are minor edifices that unquestionably celebrate their subject, and their replacement ought to be considered a healthy sign of a developing and vibrant society. Buildings however serve a profound social purpose so there needs to be exceptional and irresistible circumstances for their removal – and this quite regardless of who built them, lived in them or funded them!

Joseph Kelly is the editor of www.agorajournal.co.uk